Review: What are the features of Effective Social Innovation Labs?

Characteristics and conditions for driving systems change

Earlier this year, the UNDP called for volunteers to join a research sprint exploring how institutions can work together more effectively on complex global challenges.

The initiative, known as C3 Labs, works with the underlying dynamics that influence collaboration and transformation. This particular call came from the food systems team, who will be launching Collaboration Labs expected in Kenya and Thailand.

Keen to move fast, the UNDP asked for 8 ‘research sprint’ teams to bring insights into best practice in: Innovation Labs, Leadership Education; Future Visioning; Organisational Change and Design, Diagnostics, AI and Finance.

Inspired by the vision of C3, I volunteered to look into Labs as approaches for driving systemic change alongside Maximo Plo, Beth Cloughton and Julian Cortes.

This is a brief summary of our headline findings from a review and analysis of 20 reports on different types of labs (social labs, policy labs, accelerators, and incubators) about how they did their best work, and what made them successful or not.

Lab Types

Innovation labs are very varied, but we identified two distinct main groups, which behave predictably depending on their roots.

Public sector innovation labs tend to focus on government service improvement, regulatory experimentation, and digital transformation. They often have bureaucratic/hierarchical structures and can be constrained by political mastery.

Social innovation labs are a broader, less scrutinised church. The materials we viewed showed trends for prioritizing inclusive community engagement issues like social justice or ecological transition. They’re often heavily networked, with horizontal/fluid structures designed for participatory governance. They can be critical of conventional institutions and the politics of those in power, pushing for radical agendas.

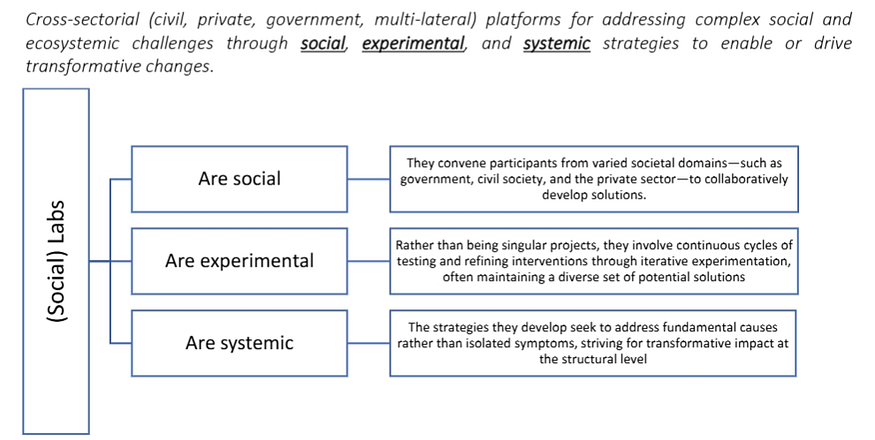

The illustration here shows how all the Labs we studied brought people from different backgrounds together.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Working Conditions

Regardless of type, the research showed repeating patterns that suggested Innovation Labs work best where the following conditions are met:

- Work is supported by a broad base — champions at multiple levels and from different perspectives are needed to achieve systems change. Partisan views need to be safely held in shared space between sectors, with institutional anchoring that doesn’t stifle independently free agents.

- Work leads to quick wins — showing the lab’s purpose in relation to stakeholders goals and communicating them well helps reinforce legitimacy.

- Value propositions are clear— so resistance from institutional partners, and other complementary structures is reduced. They can easily understand why, how and what the Lab can do to help to amplify, de-risk or innovate for mutual benefit.

- Projects are methodically planned — they align well with partners objectives, are properly resourced and map pathways for scaling successful prototypes. These measures reduce the risk of labwashing with fine words but little impact.

- A long view prevails — allowing labs to repeat and develop innovations through several cycles. It takes time and consistent advocacy with strong partnerships to adapt processes and build capacity. Training, monitoring and support is important (at least) until new approaches have successfully embedded in the system.

Participation

We also noted early/sustained inclusion of diverse stakeholders was a very common key strategy. The logic suggests a wide range of perspectives makes it easier to convert abstract ideas into practical realities that work in different conditions.

The labs in our study frequently used tactics like these below to promote participation from the margins:

- Inclusive recruitment — actively seeking marginalised and diverse applicants to ensure equity and broad perspectives.

- Ethnographic fieldwork and interviews — spending time on in-depth, qualitative research to gather insights from communities of interest before formal workshops begin.

- Rhythmic engagement — planned cycles of ongoing interaction through workshops, meetings, check-ins etc. to foster trust, learning, and continuity.

- Storytelling and personal development techniques — to increase empathy with under-represented groups and to make their needs and experiences central to the design process.

- Inclusive advisory panels or steering groups — giving marginalised voices formal roles with influence on lab direction helps with accountability and bolsters legitimacy.

Frameworks/Methods

While the reports we reviewed featured a lot of different methods, we were able to pick out five techniques that were more commonly used. They were:

- Human-Centered Design (HCD) — to understand the needs and perspectives of the people the lab aims to help. It’s highly participative, allowing users to generate ideas and test solutions.

- Stakeholder Mapping — to be clear who (people, communities, organizations etc.) has an interest in/influence on the lab’s work.

- Problem Framing Sessions — to collaboratively define and understand root causes and different dimensions of the problem a lab is trying to solve.

- Co-creation Workshops — to bring stakeholders together to generate ideas and design solutions . It differes from HCD by involving wider stakeholder interests into the innovation process.

- Rapid Prototyping —to test potential solutions in fast, low cost ways for early feedback in the development process. Allows iterative refinement based on real-world reactions.

Conclusions

Our report concluded that if C3 Labs wished to run an Innovation Lab (or Labs), they would need to:

- Negotiate strong support in advance, including a broad base of champions at many levels and followed up by deep and sustained stakeholder engagement.

- Be very clear about the value proposition, and confident about showing quick wins to build confidence

- Ensure engagement strategies paid close attention to marginalized groups in reliably cyclical and relatable ways.

- Commit to experimental long term approaches, allowing non-linear, adaptive learning with successive pilots to scale according to context.

- Invest in systems thinking capacities across the board to promote replication, policy integration and mindset shifts

- Evaluate with rigour, critiquing existing frameworks and definitions which may constrain potential

For more detailed examples and case histories, you can dive into the full set of reports (2012–24) here. If you have additional insights, please get in touch with the C3 Labs team.

Leave a Reply